The four principles of Tea

Through Chado, we try to create an atmosphere combining the four principles of chanoyu——Wa, Kei, Sei, Jaku; harmony, respect, purity and tranquility. Harmony is the result of interaction of the host and the guest, the food served, and the utensils used with the flowing rhythms of nature.

Through Chado, we try to create an atmosphere combining the four principles of chanoyu——Wa, Kei, Sei, Jaku; harmony, respect, purity and tranquility. Harmony is the result of interaction of the host and the guest, the food served, and the utensils used with the flowing rhythms of nature.

The principle of harmony means to be free of pretensions, walking the path of moderation, and never forgetting the attitude of humility.

Respect is the sincerity of heart that liberates us for an open relationship with the immediate environment, our fellow human beings and nature, while recognizing the dignity of each.

Purity is cleanliness of the body and things surrounding us. Sweeping and cleaning are the very first steps in the training of tea. Before we enter the tearoom, we rinse, purifying our hands. During the preparation of tea, the host cleans the tea container and tea scoop, although they have already been cleaned in the preparation room.

The host is cleaning his own heart through purifying these utensils. Also through this act, the host concentrates his mind.

The last principle is Tranquility. Free from worldly and impure desires, one attains a peaceful and tranquil mind.

This is the state of mind that comes with constant practice of the first three principles, Wa, Kei, and Sei, in our everyday lives.

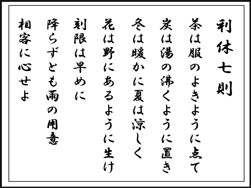

The Seven Rules of Rikyu

Make a delicious bowl of tea.

Lay the charcoal so that it heats the water.

Arrange the flowers as they are in the field.

In summer suggest coolness, in winter, warmth.

Do everything ahead of time.

Prepare for rain.

Give those with whom you find yourself every consideration.

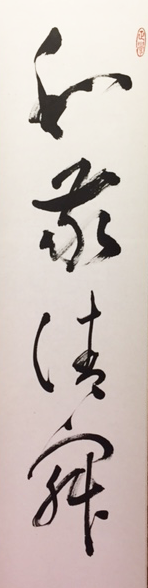

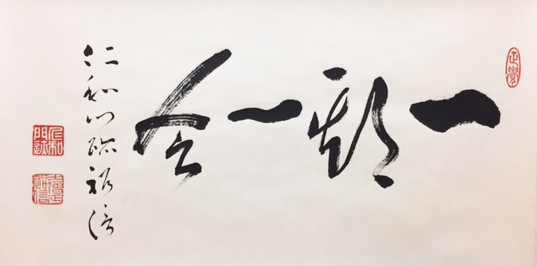

Ichigo, Ichie

Chanoyu is primarily an act of sharing between the host and the guests. It is a way of bringing people in touch with each other, no matter who they are, or where they come from. This gathering can never be repeated, even if there is the same manner of preparation, and the same host and guests. Therefore in this precious moment, the host serves a bowl of tea with all his heart, and the guests partake of it knowing that they can never experience it again in quite the same way.

This ideal is expressed in the phrase ‘Ichigo, Ichie’,’One meeting, one opportunity’, or ‘A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity’.

A SHORT HISTORICAL SKETCH CHANOYU

In the late twelfth century, a scholar monk Eisai went to China to study Buddhism and returned to Japan to find the Zen sect. Tea seeds which he brought back were cultivated in the mountains of northern Kyushu. Also seeds were given to the priest Myoe of the Kozanji temple in Kyoto. Perhaps due to the fertility of the land, the tea plants multiplied and flourished there. This is said to be the beginning of the Japanese tea plantations.

Historical records show that during the twelfth century, powdered tea such as we use today was primarily offered in Buddhist ceremonies, and was later introduced to the aristocracy and upper class samurai as a medicine. While tea was being offered in religious high prizes, in which people tried to distinguish between teas from different plantations. The contests became too extravagant and were prohibited in the fourteenth century. Consequently, a more orderly etiquette and higher moral standard came to be expected. This gradually led to the development of Chado, the Way of Tea, in a later period.

In the late fifteenth century,The Ashikaga Shogun,Yoshimasa, built a villa in Kyoto which was later called Ginkakuji, the temple of the Silver Pavilion. Within the Ginkakuji complex, Yoshimasa built a private place of worship in which is a small room said to be, were Yoshimasa`s tea masters. Shuko(1422−1502), a monk from Nara, became a disciple of Ikkyu, abbot of Daitokuji temple in Kyoto. Shuko was responsible for transforming the hitherto extravagant tea parties into a simple and serene spiritual practice. In contrast, Noami developed an aristocratic style of tea. Shuko`s spiritual successor was Takeno Jo`o (1502−1555). He was the first to formulate the ideal of wabi, seeking the honest, humble and subtle form of tea.

Among the numerous followers of Jo`o, SenRikyu(1522−1591)was outstanding.

Born to a prominent merchant family in Sakai. From the age of nineteen, he was instructing Noami and the subtle, rustic “wabi tea” of Shuko and Jo`o.

He transformed the simple act of serving and drinking a bowl of tea into a way of life.

For the past 400 years, the practice of Tea has been continued by the descendants and disciples of Rikyu. The tea we are presenting today is of the Urasenke tradition of tea. The present head is Sen Soshitsu,the sixteenth generation direct descendant of Sen Rikyu. Under his leadership, there are more than two million students in Japan and throughout the world.

(The English version is drawn mainly from the transcript of the International Seminar Lecture by Urasenke Foundation.)